Inside Science News Service

December 12, 2008

Medical Imaging Shows Gymnasts Sustain More Types of Injuries than Previously Thought

By Jason Socrates Bardi

ISNS Contributor

Chicago, IL -- Radiologist Jerry Dwek still remembers sitting on his parents' arm chair as a boy in 1972, watching Soviet gymnast Olga Korbut. She had just executed a perfect backwards somersault dismount off a balance beam in Munich, Germany -- the first in the history of the Olympics. Dwek's mother was so excited she yelled to his father in the next room, "Al, you have to come see this, she jumped off the bar backwards!"

That moment, so imprinted in Dwek's memory, left a lasting impression on the sport as a whole. It marked the beginning of a growth in popularity and participation of gymnastics at all levels in the United States. Today, according to USA Gymnastics, the sport's governing body, more than 5 million adults and children over the age of 6 participate every year, and more than 900,000 of them do so "frequently" -- practicing or competing 100 days out of the year or more.

That moment, so imprinted in Dwek's memory, left a lasting impression on the sport as a whole. It marked the beginning of a growth in popularity and participation of gymnastics at all levels in the United States. Today, according to USA Gymnastics, the sport's governing body, more than 5 million adults and children over the age of 6 participate every year, and more than 900,000 of them do so "frequently" -- practicing or competing 100 days out of the year or more.

With so many children and their parents practicing gymnastics every year, there are also many injuries. In a study published early in 2008 in the journal Pediatrics, researchers at Nationwide Children's Hospital found that some 27,000 gymnastic-related injuries are reported annually.

Besides the obvious and immediate bruises, fractures, and sprains, many gymnastics-related injuries occur over time. These injuries may not be due to single incidence, says Dwek. Gymnastics includes many high-impact exercises that require heavier wrist loads and greater wrist extension than do many other sports. Certain gymnastic movements can place unusual stresses on the skeleton, and because they are repeated over and over, they can lead to chronic problems.

Now Dwek and his colleagues have done a retrospective clinical study that suggests the existence of a broad spectrum of these chronic injuries associated with the repetitive stresses of gymnastics. "The range of injuries varies much more widely than previously thought," he said last week at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America

Dwek's study looked at 125 MRI exams taken of adolescents at Rady Children's Hospital in San Diego over a two-year period. MRI, or magnetic resonance imaging, is a common non-invasive technology used to diagnose injuries to bones, ligaments, and other tissues deep within the body. Their analysis revealed that a dozen of these adolescents were female gymnasts with chronic wrist or hand pain.

They then examined the MRI scans carefully for injuries to the bones and soft tissues, uncovering, a spectrum of associated injuries. Included among these was a classic chronic injury that occurs in children and adolescents known commonly as gymnasts' wrists.

They then examined the MRI scans carefully for injuries to the bones and soft tissues, uncovering, a spectrum of associated injuries. Included among these was a classic chronic injury that occurs in children and adolescents known commonly as gymnasts' wrists.

It is an injury to the part of the arm where the radius, one of the two major bones in the forearm, meets the wrist. The radius plays a crucial role in gymnastics and is constantly impacted in some routines, such as floor exercises for girls or the pommel horse for boys. In these routines in some positions, the radius can take nearly all the load of some movements.

Problems arise because at the end of the radius bone is a structure called the radial growth plate -- where a child's growing bone adds length. In gymnast's wrist injury, the radius may fracture or grows irregularly. Cartilage can grow into the bone's growth plate in an inappropriate manner. In an X-ray or MRI scan, this condition is easy to spot because the normal sharp line of the growth plate appears frayed because of the injury.

In extreme cases, the injury can cause deformities and damage to the radius and other bones and ligaments in the arm. It can lead to early fusion of the radial growth plate, a shortened radius and early arthritis and require orthopedic surgery to shorten the other bone in the forearm so that the wrist fits back into place.

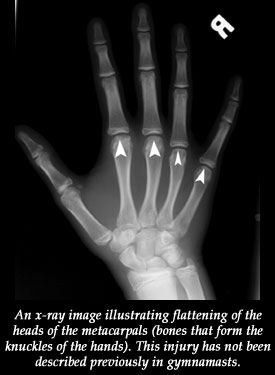

In their study, Dwek and his colleagues found that while growth plate injuries predominate in younger children who have the fastest growing bones, after children turn 13, the pattern of chronic injuries may not be limited to gymnast's wrist. Other injuries are also common, including some to the elbows, wrist, and knuckles that have not been described in the literature in association with gymnastics.

These sorts of injuries are probably due to chronic repetitive trauma, says Dwek. They include abnormal bone growth or abnormal bone loss. There were girls in the study who had unusual inflammation in their hands. Their MRIs also showed a flattening of the knuckles and knuckle "necrosis," or tissue death.

Though he does not know which particular exercises to blame, Dwek suggests that the relationship between gymnastics and stress injuries is an area that should be explored further. Meanwhile, he says, his current study underlines the need for doctors, young gymnasts, and the parents of young gymnasts to be aware of the existence of this spectrum of stress-related gymnastics injuries.

"Parents and doctors need to be aware that injuries are not just limited to the wrist and not just limited to elite athletes," says Dwek. "Injuries in gymnasts occur in elite and non-elite groups -- any child who is in gymnastics can have them."

"This is a very important study, and it highlights the fact that MRI is a powerful tool that gives us insight into disturbances of the growing skeleton," says John A. Carrino, an associate professor of radiology and orthopaedic surgery at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore who was not involved with the research. "MRI can identify injuries before there is permanent damage and while there is still a window of opportunity for treatment."

"The study also will help raise awareness that too much force on growing bones is not good," Carrino adds. "Parents need to understand that there may be value in pushing their children -- but not too far,"

Dwek's advice to parents: when a little girl complains of pain, take it seriously. And they should always tell any doctor seeing their son or daughter that the child is a gymnast -- even if they are no Olga Korbut.

More information:

- The American Academy of Pediatrics lists a number of common gymnastic injuries and gives guidelines for parents, coaches, young gymnasts and their pediatricians.

- The American Association of Physicists in Medicine has a brochure describing diagnostic medical imaging. The PDF is available for viewing and downloading.

This story is provided for media use by the Inside Science News Service, which is supported by the American Institute of Physics, a not-for-profit publisher of scientific journals. Please credit ISNS. Contact: Jim Dawson, news editor, at jdawson@aip.org.